I recently undertook this internship with the Stirling Smith as a Masters student at the University of Edinburgh in Modern and Contemporary Art: History, Criticism and Curating. I focused on Thomas Stuart Smith’s three portraits of black men painted in 1869, and I sought to recognise their position within the canon of black Victorian portraiture, and within the recent upheaval of racial justice issues in the UK and Scotland.

It is not immediately evident that Thomas Stuart Smith had any direct links to slavery, his artistic exploits being funded in the most part by his banker uncle Alexander Smith. However, his father’s (Thomas Smith) history is somewhat murkier: he worked as a secretary and accountant of the Canada Company, and was thus deeply involved in the colonisation of Canada. Furthermore, we know he was a merchant in Cuba, where slavery boomed in the years of his presence, in line with huge sugarcane exports. Although Smith the younger lost the letters from his father that could detail his exact involvement, it is important to be aware of these possible ties. It is also important to note, as Jan Marsh outlines in her exhibition catalogue Black Victorians (2005), that the expanding art world and market that Smith was greatly involved in owed a lot to British prosperity at the time, which benefitted largely from the trans-atlantic slave trade, despite slavery’s abolition in Britain in 1833.

It is not immediately evident that Thomas Stuart Smith had any direct links to slavery, his artistic exploits being funded in the most part by his banker uncle Alexander Smith. However, his father’s (Thomas Smith) history is somewhat murkier: he worked as a secretary and accountant of the Canada Company, and was thus deeply involved in the colonisation of Canada. Furthermore, we know he was a merchant in Cuba, where slavery boomed in the years of his presence, in line with huge sugarcane exports. Although Smith the younger lost the letters from his father that could detail his exact involvement, it is important to be aware of these possible ties. It is also important to note, as Jan Marsh outlines in her exhibition catalogue Black Victorians (2005), that the expanding art world and market that Smith was greatly involved in owed a lot to British prosperity at the time, which benefitted largely from the trans-atlantic slave trade, despite slavery’s abolition in Britain in 1833.

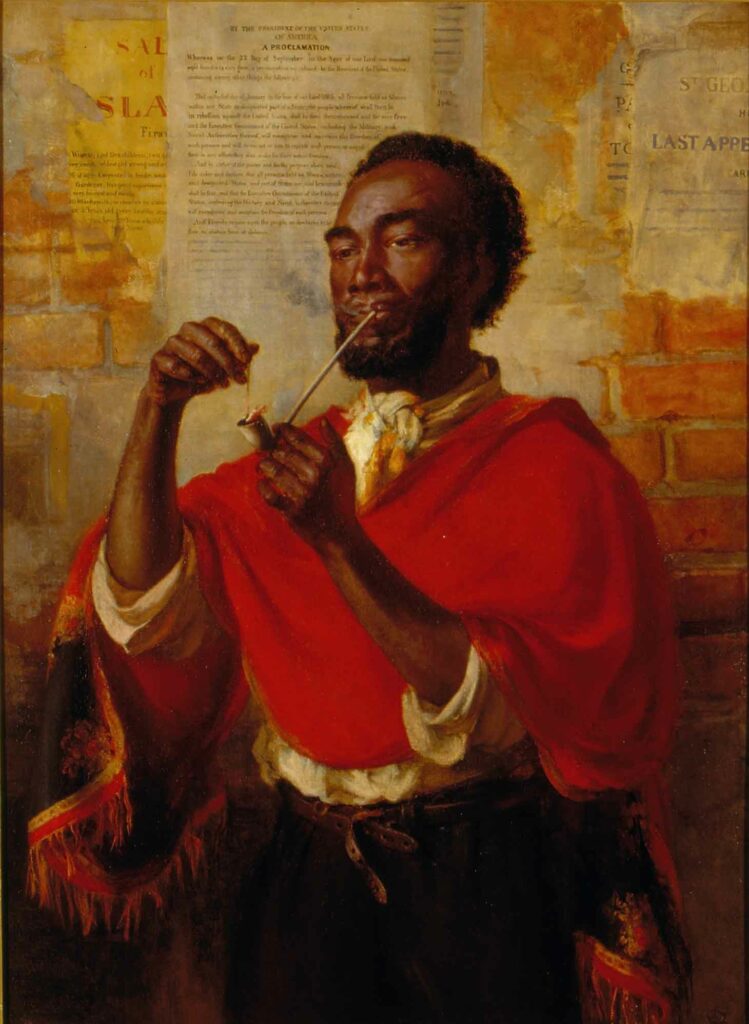

The most vital painting of this collection is The Pipe of Freedom, which was rejected by the Royal Academy for the summer exhibition in 1869 and instead hung in a Select Supplementary Exhibition in Old Bond Street. Smith claims that this rejection was based on political grounds, and although there is no evidence for this, there were indeed a growing number of alternate gallery spaces at this time. In this portrait, the model sits before the Emancipation Proclamation, lighting a pipe. There is a possible significance in this act of lighting, as other pipes in the RA collection are already lit. As a symbol of ignition, the lighting of the pipe depicts the burning of tobacco — a huge product of slavery in the U.S. In terms of the model, it is unlikely that Smith visited the U.S. or Africa, and he also noted in a letter (first transcribed in 1881) that he altered the complexion of the sitter to look partially Native American. This lack of specificity (intentionally or unintentionally) speaks to the loss of cultural history and familial connections of enslaved peoples who were torn from their lands and belongings. Smith also notes in the letter that the scarf over the shoulders of the man belongs to his wife, which brings the enslaved women of the time into light. The lack of black women in Victorian portraits as a whole echoes this hidden history. The textuality of the inclusion of the proclamation represents the greater narrative of civil rights, not only of the American Civil War, but even further into present issues of racial justice. The inclusion of narrative implicates the contemporary viewer into the Victorian painting: where do we stand in this narrative?

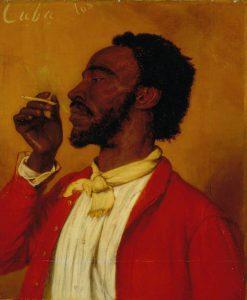

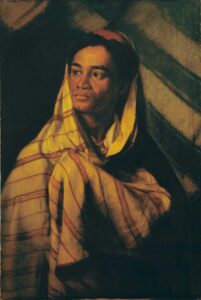

In the second painting, A Cuban Cigarette, the model seems to be sitting in a post-emancipation setting, as his pipe is already lit and his clothes are of a higher class — celebrating freedom. The third painting, A Fellah of Kinneh, presents an ordinary man from North Africa — probably Egypt, as Jan Marsh notes that ‘Kinneh’ probably denotes the town of Qena. This work was hung in the 1869 RA Summer Exhibition, however, Smith voiced another grievance here, suggesting that the painting was hung ‘out of sight’. We have no evidence of its positioning — although Jessica Feather has noted that the 1869 Exhibition occupied a purpose-built space for the first time, with new hanging arrangements ‘intended to improve visibility’.

third painting, A Fellah of Kinneh, presents an ordinary man from North Africa — probably Egypt, as Jan Marsh notes that ‘Kinneh’ probably denotes the town of Qena. This work was hung in the 1869 RA Summer Exhibition, however, Smith voiced another grievance here, suggesting that the painting was hung ‘out of sight’. We have no evidence of its positioning — although Jessica Feather has noted that the 1869 Exhibition occupied a purpose-built space for the first time, with new hanging arrangements ‘intended to improve visibility’.

Although Victorian portraiture is seen often as a white discipline, Smith’s paintings are not alone and sit within a canon of black representation. Unfortunately, black figures were most often marginal and presented as servants, or at the very least as subjects of a ‘superior’ British culture. Black models were also not always available, and so dark tones were sometimes fabricated. When abolition arose as a theme in portraiture and in other paintings, white self-congratulation was a common theme, in which the white Briton was presented as a saviour, and the black subject presented as an exotic Other. Even when the black subject was given agency, as in The Pipe of Freedom, Otherness is still clear in the colonial gaze of the white viewpoint. Furthermore, progress was not linear, as the scramble for Africa in the 1880s ignited a greater level of racial intolerance in society and racist depictions in art. The Emancipation Proclamation too was not the universally emancipatory moment that we like to imagine, as the hardships of African Americans continued over the century and into our own. We must imagine Victorian racial paradigms complexly, and thoroughly appreciate but not deify positive moments.

Narrowing down to the locus of Stirling, abolition was a hugely debated and understood issue. Archives show a great number of lectures and discussions of the American situation, mostly in local churches such as the Free North Church and Erskine U.P. Church, and the School of Arts. Guest lecturers, including ex-enslaved people such as William Craft, interacted with locals in nuanced discussion. For example, an 1866 report on the United States by Stirling M.P. Laurence Oliphant notes that abolition will not solve all the problems facing African Americans, who will ‘not be allowed to buy or rent land’ and who are now ‘between the upper and the nether millstone’. Furthermore, in a lecture in the Union Hall in September 1864 by Rev. Anderson of New York, an understanding is shown of Britain’s role in American slavery: ‘by our immense and constantly increasing demand for slave-grown cotton we had been practically the parties on whom American slavery depended on for its very existence.’ It is likely that Smith was aware of these discussions, as he often attended lectures in his local area.

As a contemporary audience to Smith’s black portraiture, we are not exempt from the progress of anti-racism and civil rights. The work and effects of the 2020 Black Lives Matter Movement are not unprecedented, as work for equality has occurred since the dawn of exploitation. Scotland too should and has taken part in recent movements, in 2020 protests but also artistic projects such as Wezi Mhura’s Scottish Black Lives Matter Mural Trail. The recently inaugurated Afro Caribbean Society of Scotland (and other more local societies) are a great resource for companies and institutions who desire to work towards ‘the elimination of inequality and discrimination’ through ‘consultation, workshops, events and anti-racist training.’ The history of slavery and colonialism still have huge ramifications in our society today, and so it is essential that we view our works through an anti-racist lens: championing black self-representation in art today whilst also examining black representations in the art of the past.

As a contemporary audience to Smith’s black portraiture, we are not exempt from the progress of anti-racism and civil rights. The work and effects of the 2020 Black Lives Matter Movement are not unprecedented, as work for equality has occurred since the dawn of exploitation. Scotland too should and has taken part in recent movements, in 2020 protests but also artistic projects such as Wezi Mhura’s Scottish Black Lives Matter Mural Trail. The recently inaugurated Afro Caribbean Society of Scotland (and other more local societies) are a great resource for companies and institutions who desire to work towards ‘the elimination of inequality and discrimination’ through ‘consultation, workshops, events and anti-racist training.’ The history of slavery and colonialism still have huge ramifications in our society today, and so it is essential that we view our works through an anti-racist lens: championing black self-representation in art today whilst also examining black representations in the art of the past.

Laura has also made a curation related to her fantastic research which you can check out on ArtUK.